Harland Sanders, the Chicken Man

In all respects, Harland David Sanders was the definition of self-made success – no matter how much that word is abused by millionaires to sell their story. He lived a life of relative poverty after his father died when he was only five years old. However, there is an important thing to go over before labeling his tale as a ground-up, self-success story; as Colonel himself put it over his two autobiographies, his tale is more about self-discovery. He found out his skill in the culinary industry in the latter half of his life and only figured out how to make money out of it much later on.

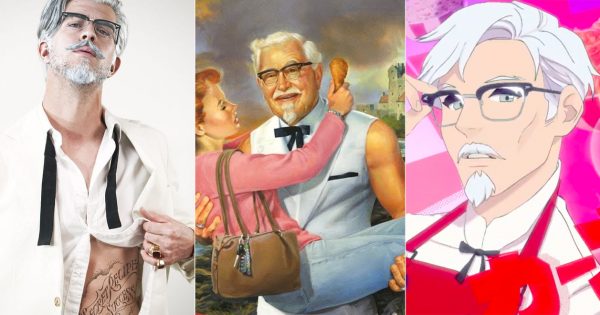

Colonel Sanders was also, in all due respects, a businessman. He played up his old Kentucky Colonel title to its limit, strategically dressing up in a white suit and a string tie while growing a goatee and bleaching it white. With the magic of the internet, baseless rumors, and KFC’s ruthless marketing schemes to sell the “southern hospitality” that their chickens and mashed potatoes somehow represent, a character was born – an old, slightly chubby man in a white suit, wearing a dapper black string tie, smiling wide and repeating “finger lickin’ good” in a thick Southern accent, now christened Colonel Sanders, about a billion miles away from the actual person Harland.

What was a “low-cost marketing tool” for a company now was their main brand image- the gentle southern gentleman became endearing for many after multiple successful TV adverts, and with the new digital age rolling in KFC slowly began to realize the full potential of this new thing called social media marketing.

2. Parasocial Relationships and Brands

In her article “Fostering Consumer-Brand Relationships in Social Media Environments: The Role of Parasocial Interaction”, Lauren Labrecque of the University of Rhode Island pinpoints two aspects of parasocial interaction to be vital to the success of social media marketing: perceived interactivity and openness in communication. Perceived interactivity is “dependent on the user’s perception of taking part in a two-way communication with a mediated persona”. Openness is not just revealing information about your brand; it can go as far as “breaking the fourth wall”, crumbling the veil of marketing for an instant to show your “true” intentions to develop trust.

Given a humanoid brand symbol whose famous image of hard work and hospitality has been forever engraved in the brains of the masses, KFC already stands at an immediate advantage. The sole fact that KFC is using a human being who once existed in this world and was a vital part of the company’s branding has given them an upper edge on marketing; they just had to translate the pre-established PSI (parasocial interaction) to the world of social media. KFC has extensively used the persona of Colonel Sanders in many of their marketing projects, not just in social media: from DC Comics collaborations to wine mom romance novellas to… a dating sim.

3. I Love You, Colonel Sanders!

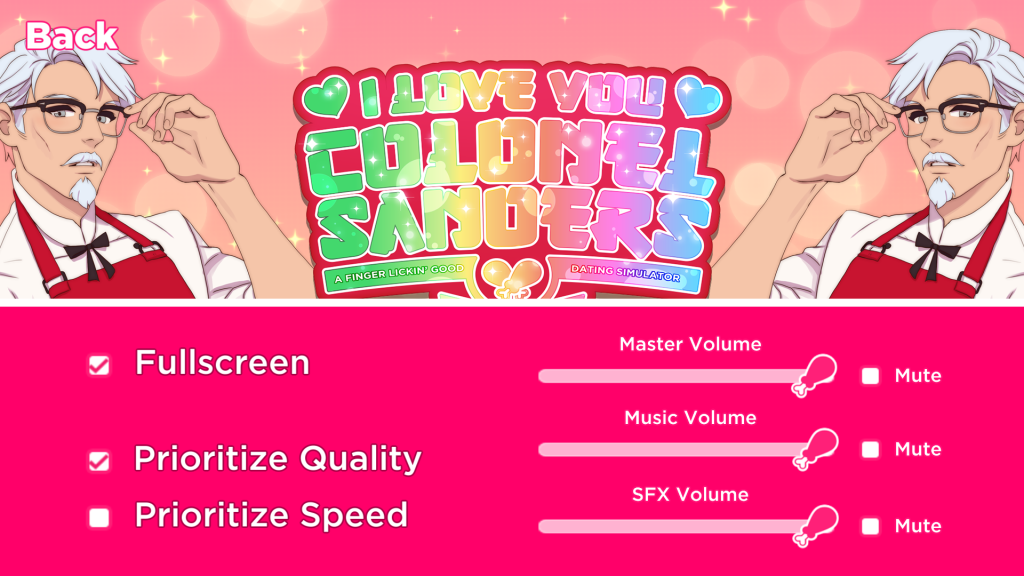

I Love You, Colonel Sanders! A Finger Lickin’ Good Dating Simulator is a 2019 dating sim advergame developed by Psyop and published on Steam for free. The player controls an ambiguously gendered protagonist (called “they” once in the entire game) who enrolls in a three-day culinary college only to fall in mad love with the titular character. The player then must win the heart of the legendary Colonel as they engage in food battles with rivals, encounter monsters, and maybe create a brand new KFC menu that you can go grab at your local Kentucky Fried Chicken store right now.

(Image Credits: AdWeek)

Colonel Sanders is only a part of KFC’s bigger marketing project to re-imagine the classic colonel for the modern audience. Chiseling a well-known brand mascot into a Michelangelo sculpture is nothing original; the Quaker bar dude got some shoulder pads and a fresh haircut in 2012 while Mr. Clean got a brand new CGI look and a handful of horny fans off the internet. KFC’s approach with campy Instagram models posing like dramatized Grindr profiles or a steamy romance novella set during Victorian England are all part of reviving the Colonel into the internet era; as they put it, KFC is trying to “make the Colonel a part of pop culture”.

Notice the air of irony that’s surrounding this whole movement. The surreal combination of Colonel Sanders, a pop culture icon engraved into the subconscious of millions, with romance, anime, and naked hunks is reflective of the ironic nature of the modern internet culture. The “modern audience” that KFC is trying to target now becomes quite clear: the denizens of the postmillennial internet age, commonly described through terms like “dank” or “edgy”. The peak of absurdity, weirdness, and the combination of two completely unrelated spheres, something that’s funny because nobody can understand what or why it is funny. Colonel Sanders game is a calculated effort of KFC to actively incorporate internet meme culture into the image of KFC.

It is also important to note the prevalence of Japanese animation (“anime”) in modern American internet meme culture and the American cultural landscape as a whole. This game draws very heavy aesthetic inspirations from modern anime. For the time being, I will define modern anime (2010s onwards) as this: the modern anime is mostly distinguished by heavy emphasis on animation quality (“sakuga”) and character archetypes (-dere branches, bishonen/bishojou, chunibyou, etc.) and a lesser emphasis on overarching themes or morals. These archetypes are important if not the sole guiding principle of the characters and narratives of Colonel Sanders.

Note: I have my own opinions about modern anime but that is beyond the scope of this post.

1. Gameplay

Colonel Sanders is a dating sim, where the player’s final goal is to seduce and romance the titular Colonel. Dating sims are characterized by branching narrative choices, where players can influence the outcome of the story through direct interaction.

Starting with something more intuitive, this game has quite unfriendly UX design. The quicksave points in this game are quite far apart from each other, and with multiple game over points that end the game right there, chugging through dialogue up until the last point of failure can feel like a chore. Having no real savepoint system also diminishes the fun of exploring multiple dialogue options or going back to see how certain choices impact the macro, hence decreasing replayability. The fact that chugging through dialogue is not easy doesn’t help much either; there are no auto skip functions or faster text speed options, and rapidly tapping spacebar isn’t really what one would consider “fun” or “interactive”.

Minor nuisances don’t stop there. Not only is the default text size quite small, there are also no text size options– a common yet crucial accessibility function that is quite important for many players, especially for such a text-heavy game. A relatively simple omission- yet it greatly diminishes approachability.

2. Narrative

One word can describe Colonel Sanders’s narrative: bland. Dialogue options are quite limited, with most of them being related to KFC products. Fried chicken-related options are often the only sensible options, with others either being outright absurd or resulting in game overs. There was one point in the game where the player tastes Colonel’s chicken for the first time; I thought that being mesmerized by the flavors of the chicken “felt right” for the situation and chose that, only to have my character transcend the material world and resulting in a game over that sent me all the way back to the beginning of the game. The game, through its seemingly diverse but actually very narrow dialogue options, forces the player to choose the “correct” option. The main problem with this is there should be no right or wrong answers in a dating simulator or any game with branching narratives; there can be a moral implication or an overarching message that is influenced by player’s actions but the whole point of dialogue options is to give player agency through a sense of influence over the game world. Why make an interactive experience when interactivity means nothing?

The PSI mentioned earlier kicks in here: the game’s limited dialogue options are a great example of perceived interactivity, where the player is lead to believe that they have control and agency over the situation when in reality they actually can’t do anything. KFC masks the actually limited options using the absurdity and irony of the other options, consuming them as humor while silently pointing at the “correct” response, which always involves a calculated brand message. The genre of dating sims, which is all about interactivity, is manipulated by KFC to be a mere perception of one – for more chicken sales.

When the player chooses the correct options, however, the game temporarily breaks down the barrier of the KFC brand and awards the player with the “sincere” image of the company; the famous backstory of the Colonel, with his thousands of tries to develop and sell the recipe, the emphasis on no cheating or taking shortcuts when making the tasty chicken and mash, even slightly “revealing” the top-secret 11 spices and herbs. And, of course, the instantly eye- and taste-captivating image of the famous Original Recipe, mashed potatoes and gravy, coleslaw, and mac and cheese. Alas, all of this is only but an illusion of sincerity; the perceived openness of communication that develops trust between the brand and the consumer. These notions of hard work and dedication to the product that the corporation displays are just mere exploitation of the real work and dedication that laborers put into their work; the backstory of the hardworking Colonel and revealing the “secret” recipe all tell the familiar tale of smoke and mirrors about “being the best friend”, of building a sense of trust, brand loyalty, and reversion of power dynamics that exist between consumers and corporations.

3. Characters

There are no qualms about the designs of the characters in Colonel Sanders– every art asset in this game is surprisingly full of character and holds up to the unique anime aesthetics. However, their writing undermines this unique design into simple archetypes that lack depth. As mentioned earlier, Colonel Sanders draws heavy aesthetic influences from modern anime- and its emphasis on character archetypes still applies here. As per genre tradition, the protagonist is a mirror image of the player. Being mentioned once in “they” pronouns, the protagonist is a mirror reflection of the player, a blank canvas with nothing but love for the Colonel. However, based on the background art of the protagonist’s room (with a large K-pop boy band poster and a small accessories box with a pearl necklace protruding) and certain context clues, it can be assumed that the protagonist is a straight cis teenage girl. Though this is quite against the genre tradition of either being a presumed male or having a set/customizable gender option at character creation, it does work for this game where the perception of interactivity is the only thing that matters.

Colonel Sanders is your archetypal bishounen, with sharp, chiseled jawline, thin but healthy overall silhouette, angled white hair, a small goatee to emphasize the “Colonel” part of the character without making him seem old or humorous, and a radiating glow of heavenly light every time he appears on screen. With distinct culinary proficiency and horseback riding skills, the feminine youth and originally homoerotic-inspired look automatically captivates attention yet keeps the presumed heterosexual relationship consistent.

Your best friend, Miriam, is used up as comedic relief, and her design and narrative role coincide almost perfectly. With a straight, braided mint twintail and dramatized pink bowties making a heavy contrast with her darker-toned skin and white chef’s uniform, Miriam’s only characteristic is making extremely small food and being anxious over everything she does. There is no character development nor an interesting conflict or chemistry between the protagonists, just a sidekick that is more or less another hurdle to overcome to get to the colonel. The only distinctly Black character in the entire game being used off as comedic relief and filler is quite telling of the depth that the game is trying to give to its characters, or the lack thereof.

Your rivals, Aeshleigh and Van Van, are the typical jock Chad/cheer Stacy bully duo. Aeshleigh is your stereotypical love rival, with her being “evil” and “mean” everywhere except when the unaware Colonel is looking. With brows held high and her demeaning eyes constantly looking down at the player while her hourglass-shaped body, watermelon boobs, and Elastine hair swings around for marketed sex appeal. Van Van surprisingly draws heavily from queer aesthetics, specifically from the muscular, tan, posing aspects of the likes of Tom of Finland or, more recognizably, the character design of earlier JoJo. A distinct star-shaped hair, protruding eyelashes, tan skin, and hunky leather jacket that highlights his broad shoulders, all of his designs screams gay. This is seemingly obvious for some JoJo fans who are already aware of the queer aesthetics of JoJo and the character archetype that Van Van is borrowing from. However, he constantly pairs around with Aeshleigh, being jealous of the Colonel and disappointed that Aeshleigh doesn’t direct any attention towards him instead.

I think now is a good time to mention how aggressively “no homo” this game is. From the aggressive use of feminine gender signifiers and stereotypes on the genderless protagonist to each character pairing being very explicitly heteroromantic or completely platonic, the narrative is forcing a very heteronormative coupling on all of the main cast. I think this can extend to KFC’s marketing strategy of not alienating their core audience; it is safe to assume that most of internet meme culture is built around cis/heteronormative male culture that is still alienated about direct queer representation while unknowingly straightwashing queer culture. Van Van is an epitome of this phenomenon and somewhat represents an unexplored potential; the fascinating, creative art of the game is downplayed by the bland narrative and characters riddled with archetypes and archetypes only.

The other three main characters – Professor Dog (Sprinkles), Pop, Crank, and Ghost, are all simple comedic reliefs that provide cheap laughs only while they appear on screen because they exist as they are. Professor Dog is funny because he’s a dog. Pop is funny because he’s just a kid who’s underqualified. Crank is funny because he’s a literal oven. The Ghost is funny because nobody pays attention to his existence. All of these characters, despite the art that at least tried to give each of them a distinct personality and some flavor, have a short and limited narrative that begins and ends with their comedic existence.

This is the main downfall of trying to create a story only with archetypes. They don’t work. When characters are no less than symbols, mere blobs of predetermined expressions, the narrative loses meaning and no thoughtful themes or messages can be told. Narratives can give archetypal characters enough flavor to give them depth, but Colonel Sanders fails in this regard too; most characters begin and end their existence in the world the moment they enter and exit the scene. The narrative is less of a cohesive story about love and romance and more of a bucketful of chicken propaganda with dank memes as the 11 spices.

4. Conclusion

From a marketing standpoint, I Love You, Colonel Sanders is a great example of a successful advergame that attracted the attention of the intended core customer base of social media users – mostly Gen Z and millennial audiences who are already aware of KFC’s brand image but feel disjointed by the good ol’ Colonel image. With the colorful, anime-inspired art, surreal dialogue options, and at least functioning writing that points the user towards KFC’s products, the game was built to be a viral marketing prop and did just that. KFC absolutely did bring back Colonel Sanders to the macro internet conscious – as an anime husbando.

From the perspective of social power difference and parasocial relationships however, Colonel Sanders is a giant red flag about the current late stage of capitalism we face: brands disguising themselves as the “best friends” of consumers through social media and memes. Social media has crumbled down the fourth wall of marketing and personal space, while memes have twisted every notion of generational disconnect and Gen Z anxiety as a one-dimensional aesthetic full of irony and self-hate. As SNS closes the sociocultural gap between individuals, corporations can disguise as a person, building “trust”, “sharing” secrets, and making their “friends” believe that they are valued, that they are the masters of the free market, that they are the ones that control large corporations through the invisible hands of supply and demand – when all that is a mere manufactured perception of agency and interactivity. Corporations are not human beings. They cannot develop trust or friendship, nor can the average consumer interact with them in a meaningful way, both personally and economically in the free market. The socio-economic power difference between an individual consumer and corporation is beyond measure; and when such difference exists, corporations essentially fully own the means of controlling wants and needs — the means of production and consumption. KFC has successfully perceived the average player into believing that there is no power difference between the two — a mutual relationship where they can empathize and laugh at ironic memes, relate with the love of anime and Japanese subculture, and share delicious food with the knowledge that the food will be delicious and trustworthy. In reality, KFC has yet again manufactured a demand for their product through carefully managed PSI and a thorough analysis of the modern demographic, using their image of the Colonel to personify them as much as possible. Under the sexy Colonel anime husbando, under all the cheap and one-dimensional characters and jokes, under the incredibly low-effort design and user experience, under the surrealist and ironic vibe around the entire game, there lies no sincerity or true notions of friendship. Under the “dank” always lies the profit motive to sell more Original Recipe.

In his later years, Harland Sanders was a salaried employee of the KFC company; he became a brand mascot, frequently appearing on commercials and touring around the world to spread the corporation’s gospel about honest work and delicious chicken. What many people don’t know is that he was highly critical of KFC using his image to sell what he thought was a bad product. He once called the mash and gravy as being “sludge” and “wallpaper paste”; he would make surprise visits to KFC restaurants and throw the food on the floor if it was unsatisfactory, in which many cases proved true. He constantly pressured executives to not change his recipe, throwing tantrums at them with such “force and variety of his swearing”, though that didn’t stop the company from simplifying the “throw away the drum chicken”-good gravy recipe. His last-ditch effort to sell honest to God fried chicken almost failed when KFC sued him for reopening his original restaurant at Shelbyville, KY under his wife’s name (the restaurant is still there- Claudia Sanders’ Dinner House). Even on his deathbed, Sanders did not stop criticizing KFC’s food as they changed their menu to cut costs and sell more; he once called the new Extra Crispy “damn fried doughball stuck on some chicken”.

Sanders died at age 90 in 1980 of acute leukemia. Despite Sanders’ protests, KFC still uses the famous colonel in most of their advertising material, glorifying his struggles as an impoverished common man as a story of self-made success into a worldwide market leader in fast food fried chicken that made $2.5 billion in annual sales revenue just last year. The KFC corporation and the Sanders brand still lives on- and KFC successfully reinstated their glorified, calculated image of the Colonel into the modern consciousness with memes, anime, and dating sims. I Love You, Colonel Sanders! A Finger Lickin’ Good Dating Simulator is an egregious example of exploitation of power relationships, personal branding, and parasocial relationships.

However, at the end of the day, the corporate machine still marches on with a white suit and a goatee, implanting demands into our minds with a sole message:

“Buy Our Chicken.”